So a while back, I received the following text from my mom:

“Why do airplanes make exhaust lines…Do they opt to do it?”

This a question that some of you may know the answer to and others may be curious about; or perhaps you know the answer, but do not know how to verbalize it. Whatever the case, it is intellectually beneficial to consider these kinds of everyday questions, especially if you are a student, recent graduate, or professional within any of the STEM fields.

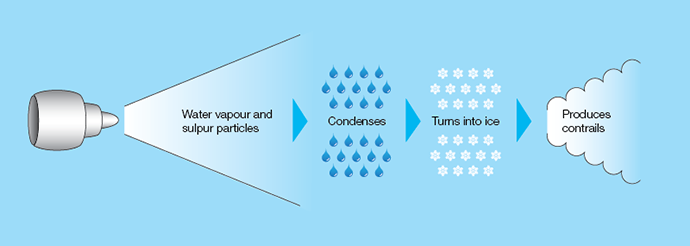

A jets exhaust gases contain a host of constituents: carbon dioxide, water vapor, unburned fuel, soot, possibly metal particulates, and oxides of sulfur and nitrogen to name a few. The exhaust gases exit the engine at a higher temperature and humidity than the surrounding atmosphere, especially at high altitudes.

From thermodynamics and fluid mechanics, we know that as altitude increases, vapor pressure and the corresponding saturation temperature (dew point) decrease. Thus at high altitudes, the vapor pressure and dew point (which determines the maximum amount of water vapor that can be contained in air prior to saturation, or the point at which the air cannot hold any further water) are low, while the exhaust gases produced by a jet engine are hot and humid. When the exhaust gases (which have a high absolute humidity) mix with the atmosphere (which has a lower absolute humidity), the local relative humidity in the exhaust jet is increased. If this relative humidity reaches 100%, the mixture becomes saturated, and any additional water vapor is condensed out of the air.

If the high altitude environment is cold enough, this water condensate can either immediately freeze or become supercooled below its freezing temperature, requiring a nucleation site upon which to begin formation of ice crystals. The previously described particulates present in the exhaust products provide just the sites (or solid surfaces) necessary for the formation of the ice crystals (and thus the freezing of the condensate). And so, whether the condensate freezes or not, millions (perhaps even billions) of droplets of water and/or ice crystals combine to form the condensation trails, or “contrails”, that we see in the wake of airplanes as they fly overhead.

As an added note, a lot can be discerned in the way of atmospheric conditions by looking at the length profile of the conrtrails. Are the contrails very solid or are they puffy and spread out? Do they go a long way or disappear quickly? Are they straight or wavy? The answers to these questions can yield a great deal of information about the temperature and humidity of the atmosphere, as well as wind and atmospheric mixing conditions. In fact, with enough known in the way of atmospheric conditions and the properties of the engine producing the contrail (as well as enough free time), one could possibly even figure out an approximate altitude that the plane is flying at!

So there you have it! That is what produces those “exhaust lines” we see in the sky. For a briefer explanation for our mothers or anyone who might have a hard time grasping this, a concise simple way to put this is: Exhaust gases are hot and humid while the air is cold and dry and so the water vapor in the exhaust gases condenses into water droplets which may or may not freeze, thus forming the cloud-like contrails left by jets.

thank you Brian – almost inquisitive and fortunate to have an ME to allow me to learn by asking!

You’re welcome, the more we can help people learn the better!

oops – “always” inquisitive